During Tygron’s Community of Practice Day, a special edition of the digital twin learning community was organized. A diverse group of professionals explored the question: how can we use digital twins to make urban challenges smarter, healthier, and more future-proof?

The session was organized by the Healthy Urban Living Data and Knowledge Hub, an independent partnership of public and private organizations. Their goal: to jointly learn, develop, and apply data-driven tools for a healthy living environment. Digital twins are a key focus in this process. They enable municipalities and partners to gain insight into complex issues, increase participation, and provide a robust policy foundation.

Municipality of Nieuwegein

Guus Welter (Quality Manager for the Environmental Act, Municipality of Nieuwegein) provided insight into how Nieuwegein uses indicators within its digital twin in Tygron. The platform supports, among other things, the housing construction monitor, which focuses on themes such as new construction, building freezes, and capacity. The municipal council has since determined that the digital model must be used structurally, although in practice this regularly leads to discussions about the interpretation of indicators. Think of the 3-30-300 rule for green spaces or the 300-meter care circle. “Every indicator sparks discussion, and that’s a good thing, because figures only prove valuable when it’s clear what you want to achieve with them,” said Welter. He emphasized that reliable data is crucial; visualizations such as 3D videos aid decision-making, but poor data can actually confuse matters. Welter: “At one point, someone was asked what the added value of a digital twin is, and someone replied that it can be a decision-making system. Well, that’s when a number of people completely lost their cool.” What he means is that the digital twin is primarily a powerful, supportive discussion tool.

Province of Utrecht

Stephen van Aken (Policy Advisor, Innovation, Healthy Living Environment, Province of Utrecht) explained how the Province of Utrecht uses the Healthy Area Development (GGO) methodology within its digital twin. The GGO acts as a scoreboard for municipalities: designs are assessed early on for air quality, noise, heat, and other environmental factors. “We’ve been working for 5 to 10 years to precisely determine the standards and bandwidths of what we consider a healthy neighborhood,” said Van Aken. This stimulates the discussion about healthy cities from the very first sketch. “Digitalization accelerates this process.” The province organized a course for municipalities and is now developing both a GGO-light and the scenario tool ZOUT (View of Utrecht). Van Aken: “We’ve noticed that it’s more successful the larger the mix of participants. You want collaboration.” Ambitions lie in standardization and expansion to themes such as soil and water, as well as area-specific standards. The common thread is that the sooner you implement the GGO, the more valuable the discussion becomes.

Costs and Benefits

Ronald Buijsse (Program Leader at Utrecht University of Applied Sciences) delved deeper into the (social) cost-benefit analysis (CBA/MKBA) of digital twins. He demonstrated that a good framework helps free up budgets and strengthen discussions with policymakers. “With digital twinning, you see that more costs are incurred in the preliminary phase, where the plans are being developed and calculated. But if that’s done well, the costs also decrease in the later phase,” said Buijsse. Other parties also benefit: project developers can contribute through prior agreements, provided the value is properly explained. Buijsse warned that without a clear analysis, the credibility of digital twins is compromised. Therefore, avoid micromanaging individual indicators and focus on the main points. “Be well prepared, because if you want to do something with a digital twin and you don’t know where the benefits lie, you won’t be in a strong position in the discussion.”

Interactive workshops

After the introductory talks, participants broke into groups to discuss various statements and issues. At the end of the workshops, the key lessons were shared in plenary sessions, with the agreement to explore the discussed issues further in subsequent sessions. These were the key findings.

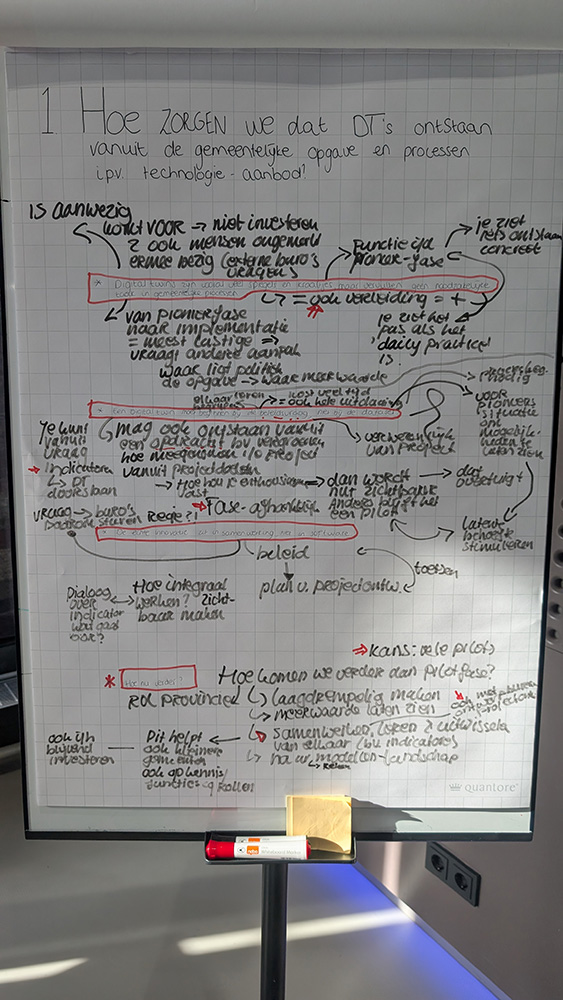

1. How do we ensure that a Digital Twin emerges from municipal tasks and processes rather than from technology provision?

Rosemarie Mijlhoff (Senior Consultant & Researcher Multistakeholder Partnerships):

“Digital twins should always start from the municipality’s own tasks, not from the technology provision. Collaboration with external parties helps to sustainably embed tools.”

2. How do we demonstrate the value of a Digital Twin for public perception and society?

Merel Backx (Healthy Living Environment Program Manager at Utrecht University of Applied Sciences): “Demonstrating benefits remains a challenge. Participants shared experiences on potential funding sources and effective ways to connect with administrators and partners.”

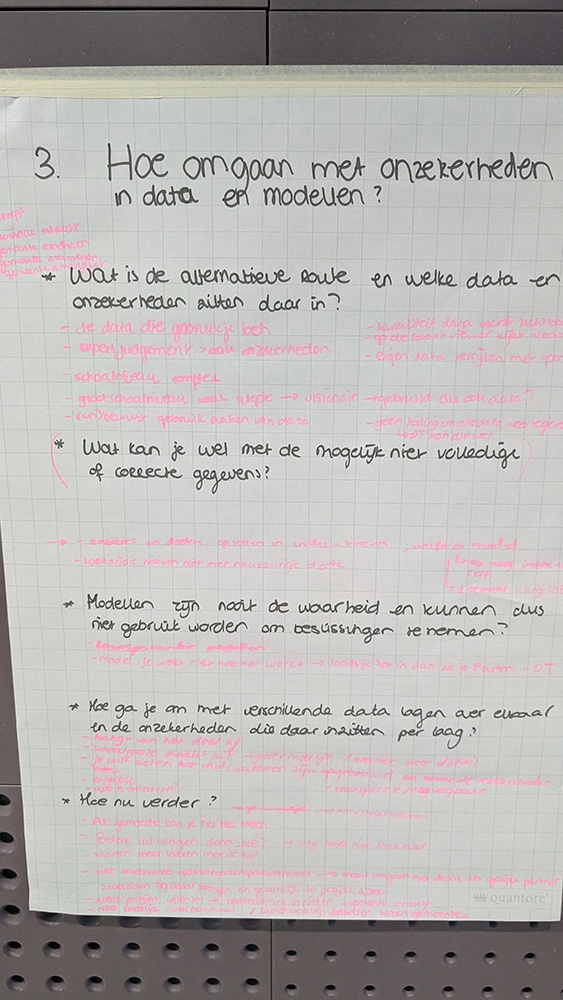

3. How to deal with uncertainties in data and models?

Milou van Muijden (Coordinator of Learning Communities at the Healthy Urban Living Data and Knowledge Hub): “Transparency in indicators is essential. Municipalities want to be able to adapt models to local circumstances to increase trust and usability.”

4. How can you handle municipal tasks flexibly?

John Joosten (Geo-information Consultant): “The group advocated for flexibility in indicators and providing them to planners early on. Visualization tools, such as the GGO, help to quickly create insight.”

About the Healthy Urban Living Data and Knowledge Hub

The Healthy Urban Living Data and Knowledge Hub is a partnership in which public and private parties collaborate to learn and innovate on the theme of healthy living environments. The DKH GSL is an independent platform that develops scientifically sound, data-driven tools and interventions and shares knowledge for a healthier urban living environment.

Digital twins are a key focus area: they offer new opportunities to gain insight into complex issues, strengthen participation, and inform policy with data and scenarios.

At DKH GSL, we look back on this session with great pleasure and are eager to follow up. The next meeting of the digital twin learning community will take place on Thursday, March 12, from 2:00 PM to 4:00 PM in Utrecht. We will then delve deeper into the four topics of the workshops. In preparation, we will identify potential directions and opportunities, so that during the meeting we can explore together how we can concretely address these issues. Would you like to attend? You can register by sending an email to info@gezondstedelijklevenhub.nl.

The introductory presentations by the Municipality of Nieuwegein (Guus Welter), the Province of Utrecht (Stephen van Aken), and the Utrecht University of Applied Sciences (Ronald Buijsse) can be downloaded here:

The comprehensive report of this meeting, prepared by the Data and Knowledge Hub for Healthy Urban Living (DKH GSL), can be downloaded here: